When product teams are building great solutions in the software domain, there’s typically a triumvirate of professional disciplines that work most closely together: design, software engineering, and product management. I spent my formative first decade in tech practicing as an interaction designer. In my second, I’ve played the role of a product manager. While I've personally never been a developer, I've had the good fortune to know some very well, among my closest family even — and hey, I did write some Basic, Javascript and HTML once upon a time. 😅

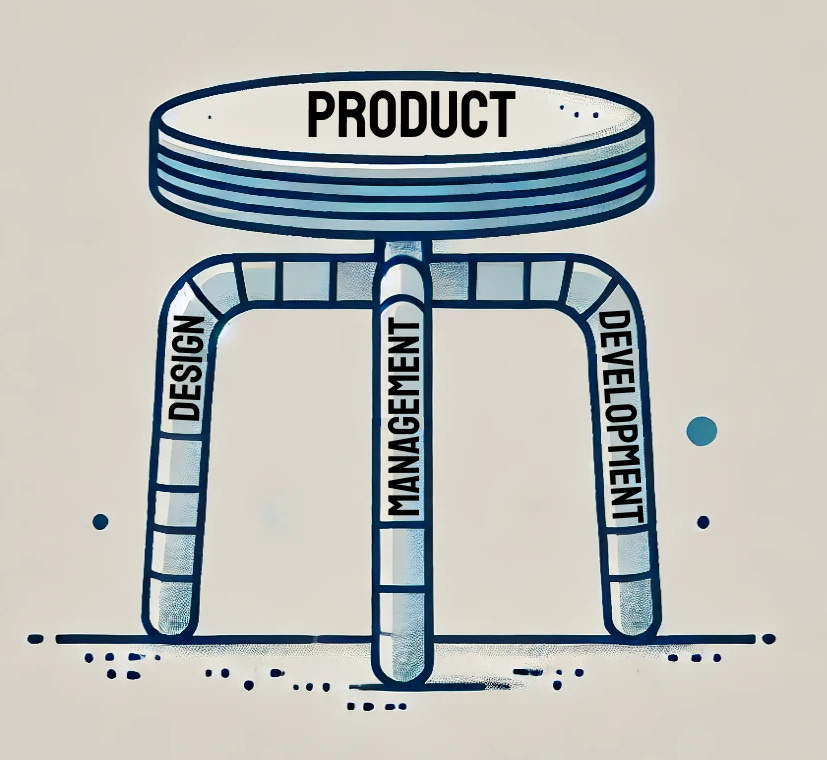

Building products is always a team activity. Design — development — product management: these three pillars form the foundation of the teams that build great products. At the awful risk of being reductive, design leadership brings vision and user-centric thinking; software engineering provides technical expertise and owns feasibility and reliability; and product management orchestrates the overall strategy, structure, and execution of the work.

None of these disciplines will achieve greatness in isolation from one another. As these disciplines operate from their spheres of concern, it's trust that acts as glue to bind them together, allowing the three disciplines to function as a cohesive unit rather than siloed specialties.

Balanced Team movement

In making this point, I am harking back to the Balanced Team movement. This powerful intersection of early agile development practitioners and design thought leaders coalesced back in 2009. Ahead of the Agile 2009 conference, luminaries including Jeff Patton, Alan Cooper, David Hussman, Lane Goldstone, Jared Spool, and Desirée Sy (and me too thanks to working at Cooper and establishing an enduring friendship with Alan and Lane!) met over a meal to discuss the commonalities between design and development. We were all passionate about improving product development practices with more human-centered values — top to bottom, left to right.

The Balanced Team movement (BT for short) burbles along today in various forums, nurtured by the hearts, minds, and hands of early devotees like Adrian Howard, and loyal ambassadors like Lane and one of my esteemed colleagues, Tom Illmensee.

Just yesterday in fact, I had the pleasure of joining a “Balanced Team in the Ether” call that was a lively lean-coffee style online gathering. Our London hostess, Martina Hodges-Schell, and participants from Spain to Vermont to Portland co-created an agenda and helped each other with business problems. Topics included “How to overcome stakeholder resistance to the balanced team practice because they want to know ‘who’s in charge,’” and “Getting senior stakeholders comfortable with ambiguity.”

I love that BT’s number one value is: create trust. The complex and cross-disciplinary activity of building great solutions benefits enormously from trusting relationships. (See my last post on trust here.) Estimating delivery timelines, negotiating feature tradeoffs, debating customer priorities, and making the many creative decisions of marketing goes more smoothly and is more enjoyable when people trust each other. As the group pointed out today, trust is often best established through the small things: following up right after the meeting as promised, for example. Showing that you care about others on a human level.

The BT movement focuses on a team having the right blend of skills and pursuing desirable outcomes together, as opposed to enforcing fixed roles, responsibilities and titles. The intent is that an effective team contain people who have the right skills to build products. Now, the specific competencies within and across research, design, development, testing, measurement and management can take numerous forms depending on what product is being built and at what scale. However, in my view the necessary skills can most basically be defined as those of understanding, definition, and communication. (For more on that, see this post about decoding the UX field.)

Balanced teams can answer these questions

Another way to understand the nature of balanced teams is that the core team possesses the ability to answer all the fundamental questions to inform the product being built. Even if they don’t have sole ownership over the answers, they will be the ones to propose the answers — it just might have to be defended or justified to other authorities (such as an executive, program manager, or steering committee) before getting the green light.

The highest-order questions a team must answer in order to build great solutions are:

Why.

Why are we pursuing this opportunity?

Why are we pursuing this opportunity and not another one?

What are the benefits to the business? To the customer? To the planet?

What are the potential harms of pursuing this opportunity, and on balance, should it be done at all?

What.

What are we going to do to solve for this opportunity?

What exactly are we doing first?

Next?

Later?

What changes about “what” we’re building in the interplay with the people we have available to do it and “for whom” we are going to do it?

For Whom.

For whom exactly are we delivering solutions around this opportunity?

What outcomes do we want to create for customers?

How will this opportunity affect people with whom our customer interact, such as their families and caregivers?

What do internal stakeholders and champions need to see?

How will it affect our internal sales team, and the customer support team?

How might we solve for this opportunity in the most sustainable and ethical way for everybody involved? (Hint: this includes the health of the team developing the solution.)

When.

When is the right time to pursue this opportunity? If not now, when?

What do we risk in starting it now? What do we risk in not starting it now?

What changes about “when” in the interplay with “what” and “how” as we go about building the solution?

How.

Once we have the inkling of a viable solution candidate, how will it be brought into being?

How might we create a lightweight initial solution to test our hypothesis with a minimum expenditure?

How might we build a more reliable, scalable and robust solution once we prove the fitness of our solution for the opportunity?

The truly balanced team will be able to determine and sustain the answers to those questions among its core constituents. Answering them well takes a cross-disciplinary effort, via investigations, conversations, collaborations, and other activities whose responsibilities are shared among the team members. Titles and roles are much less material than the skills of each individual.

In many organizations, as proposed above, a core team of three individuals will comprise somebody trained in user experience research and design, somebody trained in development methodologies, and somebody trained in strategy and management methodologies. Let’s picture the tried-and-true metaphor of a stool holding up the body of product — with three legs of design, development and management (or perhaps in a highly-resourced organization, four legs of design, development, and management, plus research).

Doesn’t operating in a balanced team sound dreamy? In practice, it’s a very powerful working model. And truly, it can begin right wherever you are now, with cross-disciplinary experiments that start as simply as open conversations and clever spreadsheets.

Lizz at Devise is a publication exploring the space of design and product management through the lens of heart-centered values and teamwork. Glad you’re here! Lizz is writing a book about building great product solutions — which involves fostering balanced teams. Her firm Devise Consulting is available at this time for engagements ranging from speaking & workshops to UX research, strategy, design, and product management services for the solution you want to deliver. Hit me up for a chat if you’d like to bring the goodness of Balanced Team principles to your product development team!